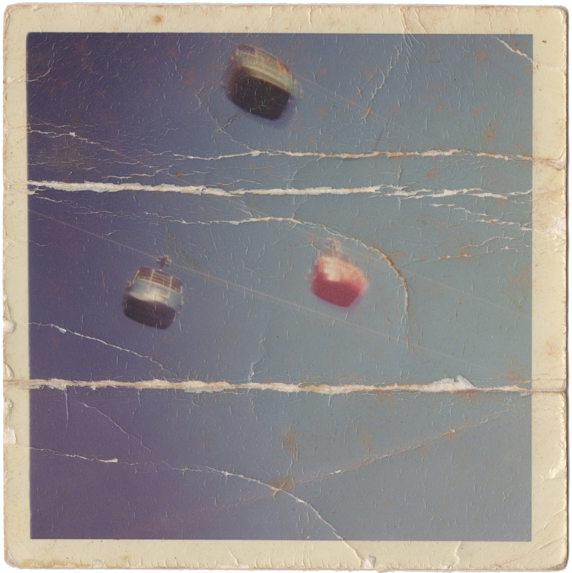

Back when photography was a “minor art,” I remember hearing it said that a photo could only be a shallower sort of thing than, for example, a painting, in the way it occupied time. The idea was that the time visibly spent by the artist on a handmade object such as a painting was to some extent mirrored, recapitulated, in the time spent on it by the viewer; whereas you could get a photograph in an instant because it had been made in an instant, or seemed to have been. And that was not good, not good at all. Well, there are exceptions, and even when it’s true it’s not completely true, but we can see the force of it. An art photo is not usually made to be an object. It’s made to be an image. And an image, an abstraction brought to the eye by an object, has no history and no age. In the extreme case of pixels on a screen, there really is no object at all. Like anything else, a photograph needs extension in space in order to have extension in time. Apart from a few cases of assertive boundary-pushing like the deliberately distressed photos of Doug and Mike Starn, art photos aren’t physically worked in the sense that a painting is, and they tend to be shielded from anything that time might do to them. In its uneasy relationship with its existence as an object, an art photo is something like an LP, and any signs of age it may have picked up in spite of everything are like surface noise: mere degradation, a distraction from the disembodied ideal. A snapshot is not like that at all. It’s just a piece of paper too, but—if we are open to this aspect of it—it’s more like a painting than an art photo is: its tangibility and its malleability actually do some work. Taken seriously as an object, a snapshot has a historical depth that an art photo doesn’t have (and doesn’t want to have). For one thing, a snapshot very often looks its age. It has lived. Its life as an object goes back to the very event it is showing us, or a little later, and, unlike an art photo, it tells us so directly: it was there, so to speak. In a way it’s nice when you find a snapshot that wasn’t as neglected and kicked around as most, but a mint-condition snapshot sacrifices a certain historical density. A second point: at least until about 1980, snapshots usually have borders—a quarter of an inch or so of white paper surrounding the image, giving the ensemble some integrity as an object (we would notice if a slice of it was gone). From our point of view here in the present, the border also certifies the snapshooter’s original framing, attests to the composition as an on-the-spot event—which, of course, takes us back instantly to that spot, that event. Although an art photo can have a border, I don’t think it is usually integral. And the framing of an art photo speaks only to the compositional intention of the photographer at some stage in the making of the print. It doesn’t usually put us in mind of the photographer snapping the shutter. Finally, it’s clear that, although people generally experience art photos as images to be looked at, they know snapshots as things to be owned and touched. We have all held them in our hands, arranged them in photo albums, turned them over to see what might have been written on the back; if we took them ourselves, we have picked snapshots up at the drugstore or printed them on our computers. The history of our families is enshrined in these objects. When we value, as objects, old photos of ancestors we may never have met, it’s because we value our history itself; whereas we probably value an art photo merely as an image. Book designers and curators often haven’t realized that a snapshot is an object all the way down and all the better for being one. Just as I did, they tend to want to assimilate snapshots to art photos, either by hiding the borders or by displaying examples that are unrealistically perfect. And when we print snapshots in books or hang them on the walls of a museum or gallery, we probably aren’t thinking about their original function, a function that was very much bound up with their existence as objects. We have no way of actually recovering what they originally did for anyone, of course. But it seems to me that an awareness of the fact of their past lives as objects can only deepen them. |

Objects and time

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment